03/08/2020

In a ministerial foreword to the recently completed

consultation on freeports, the authors â led by Rishi Sunak - waxed almost lyrical.

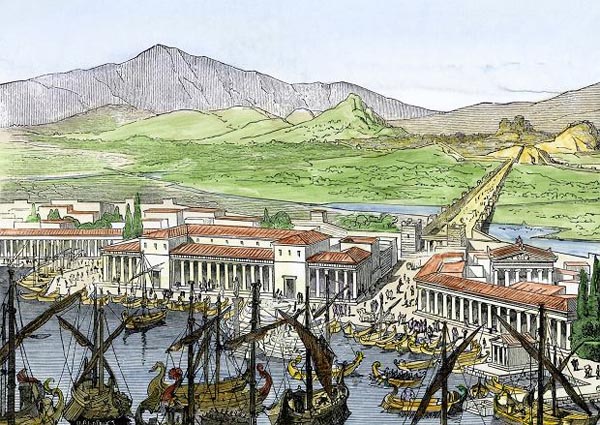

In the Ancient World, they wrote, Greek and Roman ships â piled high with traders' wines and olive oils â found safe harbour in the Free Port of Delos, a small Greek island in the waters of the Aegean. Offering respite from import taxes in the hope of attracting the patronage of merchants, the Delosian model of a "Free Port" has rarely been out of use since.

They then go on to assert that this is because freeports still offer that same story of trade and prosperity across the modern world. From the UAE to the USA, China to California, global freeports support jobs, trade and investment. They serve, we are told, as humming hubs of high-quality manufacturing, titans of trans-shipment and warehouses for wealth-creating goods and services.

And, for that reason the government wants to recreate the best aspects of international freeports in a "brand-new, best-in-class, bespoke model", which they have out in their 48-page consultation document.

Interestingly, they set out four main benefits from using the freeport system. The first is "duty suspension", where no tariffs, import VAT or excise are to be paid on goods brought into a freeport from overseas until they leave the freeport and enter the UK's domestic market.

The next is what is called "duty inversion". If the duty on a finished product is lower than that on the component parts, a company could benefit by importing components duty free, manufacturing the final product in the freeport, and then paying the duty at the rate of the finished product when it enters the UK's domestic market.

The third possible advantage is duty exemption for re-exports. A company could import components duty-free, manufacture the final product in the freeport, and then pay no tariffs on the components when the final product is re-exported.

Finally, there are simplified customs procedures. In this context, we are told that the government intends to introduce streamlined procedures to enable businesses to access freeports.

However, by various mechanisms, some of which I discuss

in this post, most of these advantages can be gained through administrative means, without taking on the disadvantages of the freeport system, arising from having to isolate the facilities and introduce enhanced perimeter security.

Specifically, a system of duty suspension already exists outside the framework of freeports, known as the

Excise Movement and Control System (ECMS). Although applied to alcohol, tobacco and energy products, the monitoring and administration system could easily be applied to other sectors. Without having to go to the trouble of creating freeports.

Similarly, if the goods are brought into the country, but are to be re-exported, there is a

temporary admission procedure which could be adopted, again without having to set up a freeport.

As for the simplification of customs procedures, this needs to be applied to all ports and, as

this example shows, could yield considerable dividends. To focus solely on freeports would disadvantage the rest of the industry.

That then leaves the so-called "duty inversion", which is the subject of a front-page report in the

Financial Times today, under the headline: "Freeport advantages for business are 'almost non-existent'". The sub-heading tells us: "Study suggests only 1% of UK imports by value could benefit from arbitrage opportunity".

Getting into the text, which adds meat to the headlines, we see the claim that government plans to build a network of ten freeports after the end of the Brexit transition period "are unlikely to have any material impact on the UK economy".

This relies on detailed data analysis by Sussex university's UK Trade Policy Observatory, which shows that duty savings are so small as to be "almost non-existent", thus providing "minimal" opportunity for businesses to take advantage of fundamental aspects of freeports.

The point raised by the analysis is that, in the United States, there are several hundred freeports, where they are known as foreign trade zones. However, they are so popular there because opportunities for tariff inversion, particularly in the automotive and petrochemicals sector, make them attractive. But, says UKTPO, that opportunity will not exist in the UK. Only around one percent of UK imports by value could benefit from the arbitrage opportunity.

"The fundamental thing is that the trade benefits of a freeport are almost non-existent", says Peter Holmes, a UKTPO fellow who co-authored the analysis. "The only benefit might be in some sort of enterprise or urban regeneration zone â but that has nothing to do with the 'port' aspect".

Delving deeper, UKTPO found that out of the 20 most imported inputs in the UK by value, accounting for around 40 percent of the UK's imports of intermediate goods, 12 were duty-free and none had a tariff of more than 4 percent.

They found that a tiny handful of sectors, including dog and cat food inputs, could offer a significant "wedge" between input and finished products, but in total these accounted for only 0.6 percent of UK imports of intermediates.

Looking at the potential tariff gap between inputs and finished products within the same sectors, the group found dairy products, starches and starch products, and animal feeds provided the greatest potential for duty savings in these sectors, but even these accounted for only 1.1 percent of total UK imports.

It would appear that the sectoral analyses to identify potential duty savings "all tell the same story", which means that introducing freeports into the UK is "unlikely to generate any significant benefits to businesses in terms of duty savings".

The

FT report goes on to tell us that the lack of obvious trade benefits from freeports has led to recent warnings from industry and anti-fraud campaigners. They are concerned that the zones will encourage fraud or, if they just offered laxer regulation or planning laws, will simply displace business.

On this, the paper cites Adam Marshall, head of the British Chambers of Commerce. He sits on the government's freeport advisory panel, and has said that business was nervous that freeports would displace jobs, not create them.

Robert Palmer, the director of campaign group Tax Justice UK, has been more scathing, predicting the chancellor's freeport plans would amount to "a few glorified industrial parks on the edge of Tory target seats in the North and midlands".

Looking at the proposal in the round, that would be exacerbated by the displacement of resource, which could be better spent on upgrading the ports network as a whole â introducing systems such as the "single window" â and improving infrastructure, the limitations of which are often the cause of restricted growth.

It really is quite remarkable, therefore, that so much energy is going into a proposal which has so little merit and which is likely to yield such little benefit. But then, this does rather typify this government which, as

Pete points out, is drifting us into failed state territory.

I suppose we can expect very little else from this government.

Also published on

Turbulent Times.